Sebastia (סבסטיה, سبسطية, Σεβαστη, Sebaste) or Shomron (שומרון, Samaria), to give it its original name, is perhaps one of the most iconic sites in Israel—the capital of the ancient Northern Kingdom of Israel—and yet it is neglected, at risk, and one of the least visited sites, for political reasons. My daughter, Amber, and I visited it chol hamoed Pesach, and we were not disappointed. I largely try to avoid politics on this blog, but here it is truly unavoidable, since it affects both access and the quality of the visit and the site. I will come back to this theme at the end.

The archaeological site of ancient Sebastia is a national park under the Israel Nature and Parks Authority, yet it is neglected. Though what was excavated in the early twentieth century is impressive, it remains under-developed and under-excavated, with no signboards or official visitor centre. The ancient site is adjacent to—and beneath—the Arab town of Sebastia, and there is a Palestinian visitor centre in the town square at the entrance to the site, which is closed to Jews (closed altogether on the day of our visit), and reportedly underwhelming as well as (at best) partial in its interpretation of the site.

Politics and geography interfere terribly at this historic site, for although the park is mainly in Area C (administered by Israel), access is through the Arab village which is in Areas A and B,1 from the village square. The square is a parking lot today, but was formerly the village threshing floor, and before that the Roman forum. Today it is dominated by a huge Palestinian flag. The Nature and Parks Authority only occasionally organises guided tours, in conjunction (necessarily because of this access issue as well as potential danger to lone tourists) with the army. Usually Israeli tourists are brought in bullet-proof buses from the nearby Jewish settlement of Shavei Shomron, escorted by IDF jeeps, although on our visit we were able to drive in our own car, with IDF personnel along the route to stop Palestinian traffic as necessary and ensure we made no dangerous turns off the designated route.

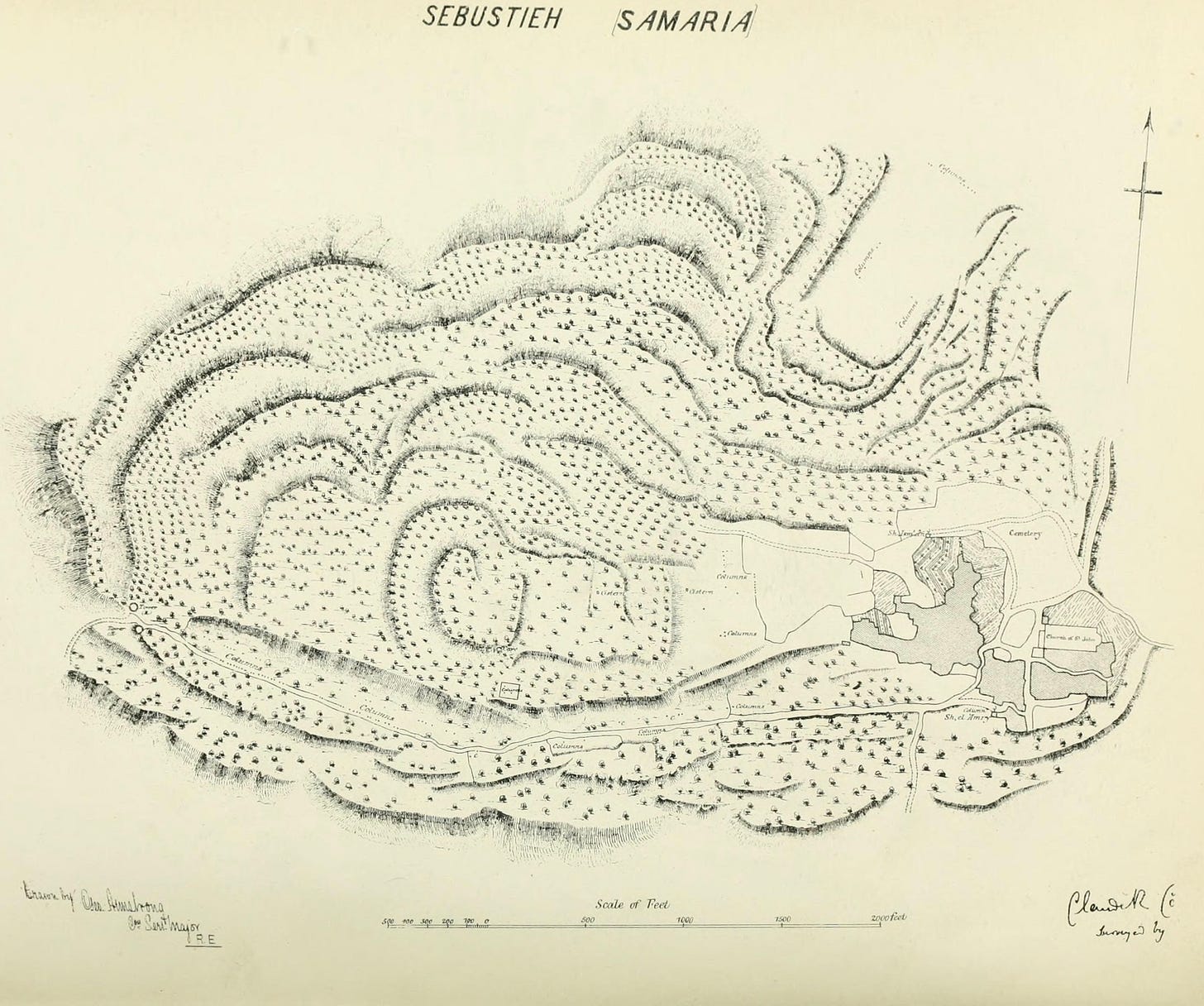

Once we turned onto the deserted country lane towards Sebastia, we hit the western (Herodian) city gate and proceeded along the famous colonnaded street (see above sketch plan), reaching the edge of the modern village and parking in the square next to the Roman forum, beneath that large Palestinian flag. The immediate area was quiet—apart from some Arab kids letting off fire crackers supposedly to frighten the tourists—and patrolled by soldiers. Only a couple of shops were open in the square, along with the ubiquitous camel rides—in this case with baby camel in tow. When we arrived, the few visitors arriving were all Israeli Jews, but by the end of our tour, large crowds of non-Jewish tourists and Orthodox pilgrims were arriving on several coaches; apparently they are able to visit at any time, unmolested by the locals, attracted by the purported tomb of John the Baptist, of which more anon.

Part of the reason for opening the site on this particular day was for the purpose of training guides for the Nature and Parks Authority. Our guide, Evyatar Nevo, who is a licensed tour guide, was extremely knowledgeable and personable, and speaks both Hebrew and English. We highly recommend him and you can contact him by email.

So what is the story of the place? After the death of King Solomon, political infighting led to the split of the Jewish nation into the kingdoms of Judah (with its capital in Jerusalem) and Israel, in the north, whose territory largely corresponded to the biblical allotments of the tribe of Ephraim and the western half of Manasseh. The sixth king of Israel was Omri (882-869 BCE), and he constructed a new capital at Shomron (Samaria), in the year 879 BCE, to replace that at Tirzah. Omri purchased the site from Shemer for two talents of silver, and the name of the city memorialises Shemer as the original landowner. Omri is mentioned in the Torah as well as in the Mesha or Moabite stele—found in Jordan, and now in the Louvre—and his line is referred to in the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III, from Nimrud in Mesopotamia, which is now in the British Museum.

The name of the northern kingdom’s capital, Shomron, is today preserved in the region of Shomron (Samaria) which forms the northern half of the territories, and in the Samaritans (Shomronim), who claim descent from the northern Israelite tribes who were not deported by the Neo-Assyrian Empire after the destruction of the Kingdom of Israel, and who continue to live just to the south east of Sebastia on Mount Gerezim. Part of the site of the ancient city is today the Arab village which preserves the ancient city’s later name of Sebastia, given to it by King Herod the Great in honour of the Roman emperor Augustus, and another nearby village, Beit Imrin, likely preserves the name of Omri. Early cuneiform inscriptions refer to the Shomron itself as Bet Ḥumri (the house of Omri).

ִשְׁנַת֩ שְׁלשִׁ֨ים וְאַחַ֜ת שָׁנָ֗ה לְאָסָא֙ מֶ֣לֶךְ יְהוּדָ֔ה מָלַ֚ךְ עָמְרִי֙ עַל־יִשְׂרָאֵ֔ל שְׁתֵּ֥ים עֶשְׂרֵ֖ה שָׁנָ֑ה בְּתִרְצָ֖ה מָלַ֥ךְ שֵׁשׁ־שָׁנִֽים

וַיִּ֜קֶן אֶת־הָהָ֥ר שֹׁמְר֛וֹן מֵ֥אֶת שֶׁ֖מֶר בְּכִכְּרַ֣יִם כָּ֑סֶף וַיִּ֙בֶן֙ אֶת־הָהָ֔ר וַיִּקְרָ֗א אֶת־שֵׁ֚ם הָעִיר֙ אֲשֶׁ֣ר בָּנָ֔ה עַ֣ל שֶׁם־שֶׁ֔מֶר אֲדֹנֵ֖י הָהָ֥ר שֹׁמְרֽוֹן

“In the thirty-first year of Asa the king of Judah, Omri ruled over Israel twelve years-in Tirzah, he ruled six years. And he bought the mountain of Samaria from Shemer for two talents of silver; he built up the mountain and called the name of the city which he built, after the name of Shemer, the lord of the mountain, Samaria.” [1 Kings 16:23-24]

Omri was not a model King, and the brief description of his 12-year reign in 1 Kings 16:25-28 only mentions in passing “the rest of the actions of Omri that he accomplished”:

“And Omri did what was bad in the eyes of the Lord, and he was more wicked than all those that preceded him. He went in all the ways of Jeroboam, the son of Nabat, and in his sin, that he caused Israel to sin, to anger the Lord, the God of Israel with their false gods. And the rest of the actions of Omri that he accomplished and his mighty deeds that he did, are inscribed in the book of Chronicles of the kings of Israel. And Omri lay with his fathers, and he was buried in Samaria, and Ahab his son ruled in his stead.”

In fact Omri’s capital may not have been the earliest settlement at the site: some scholars believe that the town of Shamir—the home of the judge Tola in the 12th century BCE (Judges 10:1–2)—may have been situated here.

As is told in the book of Kings, Omri’s successors did not please G-d, and his son, Ahab (869-850 BCE), erected an altar and temple to Baal there, after he married Jezebel, daughter of Ethbaal, king of Sidon. Famously, Elijah the prophet challenged Ahab and Jezebel and the prophets of Baal, saying “I have not brought trouble upon Israel, but you and your father's house, since you have forsaken the commandments of the Lord, and you went after the Baalim” [1 Kings 18:18].

The remains of the Israelite palaces, dated to the time of Omri and Ahab, were excavated in 1908-1910 by the Harvard Expedition (see later for more on their work), built in two distinct phases to a royal size and construction quality. The palace of Omri was enlarged during the reign of Ahab by the construction of a casemate type wall around the original palace. Two rock-cut caves found adjacent to the palaces are thought possibly to be the burial places of Omri and Ahab.

The city was besieged by King Ben-Hadad, the king of Aram, during the reigns of Ahab and his son, Jehoram, suffering starvation so that “a donkey's head sold for eighty silver pieces and a quarter of a kab of doves’ dung sold for five silver pieces” (2 Kings 6:25). During the reign of King Jeroboam, son of Joash, Shomron rose again to greatness with the restoration of the kingdom’s borders from Hamath to the Mediterranean sea. Remains of the castle from this period have been excavated at the top of the hill close to the southern wall. This and other castles at various times became palaces of prosperity and decadence—as evidenced by expensive Phoenician-style ivories and other objêts d’art from the period unearthed on site, which can be seen in the Israel Museum and the Rokerfeller Museum, both in Jerusalem—so that the prophet Amos prophesied the city’s destruction:

“Hearken to this word, O cows of Bashan which are on Mount Samaria, who oppress the poor, who crush the needy, who say to their lords, "Bring that we may drink." […] I have overthrown some of you like God's overthrow of Sodom and Gemorrah, and you were like a brand plucked from burning, but you have not returned to Me, says the Lord. Therefore, so will I do to you, O Israel; because I will do this to you, prepare yourself to meet your God, O Israel.” [Amos 4:1, 10-11]

These ivory inlays may relate to the “ivory house” of King Ahab referred to in 1 Kings 22:39: “The remainder of the deeds of Ahab and all that he accomplished and the ivory palace which he built and all the cities that he built are written in the book of Chronicles of the kings of Israel.”

In 722 BCE, during the reign of King Hoshea, son of Elah, the city was destroyed after a siege by King Sargon II of Assyria. With the exile of the city’s inhabitants, the kingdom of Israel was brought to an end, and Shomron was settled with Assyrian colonists from Babylon, Cuthim and elsewhere. The city became an administrative centre, regarded as a provincial capital, under Assyrian and later Babylonian and Persian rule. The city was again destroyed by Alexander the Great in 331 BCE, who then repopulated it with Macedonian soldiers. Its alien Hellenistic culture was contained within walls with round towers, one of which has been excavated on the north side of the hill, above the theatre.

The city was destroyed once more by the Hasmonean king John Hyrcanus in 108 BCE. It was rebuilt by Pompey in 63 BCE, when Hellenized Samaritans and the descendants of Macedonian soldiers took up residence there. However its final great flowering culturally was under King Herod the Great who was given the city and, in 27 BCE, rebuilt it and—as mentioned—renamed it Sebastia (the Greek version of the honorific Augustus) in the honour of the Roman emperor Augustus (Gaius Octavius). Herod built a temple in the city dedicated to Augustus, which was constructed on an elevated platform in the city’s acropolis. Some six thousand gentile veteran colonists, who had fought alongside Herod and helped him secure the throne, settled the city, in whose lower section was a large hippodrome whose columns survive in situ. The city was huge, and Herod encircled it in walls constructed with his signature Herodian dressed masonry. An aqueduct supplied the city with water from the wells of Shechem (Nablus) to the south east, which remains the village’s water source until today.

In the year 7 BCE, in the throes of his paranoia, Herod had his sons Alexander and Aristobulus IV transported to Sebastia and executed, by strangulation, for treason. Their bodies were carried at night to Alexandrium (Sartava), and buried alongside their maternal uncle and other family members, as recorded by Flavius Josephus in his Antiquities of the Jews. Josephus describes Herod’s building works:

“Since therefore he had now the city [Jerusalem] fortified by the palace in which he lived; and by the temple: which had a strong fortress by it called Antonia; and was rebuilt by himself; he contrived to make Samaria a fortress for himself also against all the people; and called it Sebaste: supposing that this place would be a strong hold against the country, not inferior to the former. So he fortified that place: which was a day’s journey distant from Jerusalem: and which would therefore be usual to him in common, to keep both the country, and the city in awe. […] And when he went about building the wall of Samaria, he contrived to bring thither many of those that had been assisting to him in his wars; and many of the people in that neighbourhood also. Whom he made fellow citizens with the rest. This he did out of an ambitious desire of building a temple: and out of a desire to make the city more eminent than it had been before: but principally because he contrived that it might at once be for his own security; and a monument of his magnificence. He also changed its name, and called it Sebaste. Moreover, he parted the adjoining country, which was excellent in its kind, among the inhabitants of Samaria, that they might be in an happy condition, upon their first coming to inhabit. Besides all which, he encompassed the city with a wall, of great strength; and made use of the acclivity of the place for making its fortifications stronger. Nor was the compass of the place made now so small as it had been before: but was such as rendered it not inferior to the most famous cities. For it was twenty furlongs in circumference. Now within and about the middle of it, he built a sacred place, of a furlong and an half [in circuit] and adorned it with all sorts of decorations: and therein erected a temple: which was illustrious on account of both its largeness and beauty. And as to the several parts of the city, he adorned them with decorations of all sorts also. And as to what was necessary to provide for his own security, he made the walls very strong for that purpose; and made it, for the greatest part, a citadel: and as to the elegance of the buildings, it was taken care of also; that he might leave monuments of the fineness of his taste, and of his beneficence, to future ages.” [Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, 15:8:5]

The city was destroyed during the Great Revolt of the First Jewish-Roman War, between 66 and 70 CE. It flourished again as a Roman colony in the second and third centuries CE, when the theatre, forum, basilica, a temple dedicated to Kora (the Roman name for Persephone, the daughter of Zeus), and a colonnaded street, the Decomanus Maximus, were built. The street was 800 metres long and 12.5 metres wide, colonnaded on both sides, forming covered walkways of more than 600 columns with shops. Stairs that rise from the street to the forum have been preserved, but are not accessible to visitors.

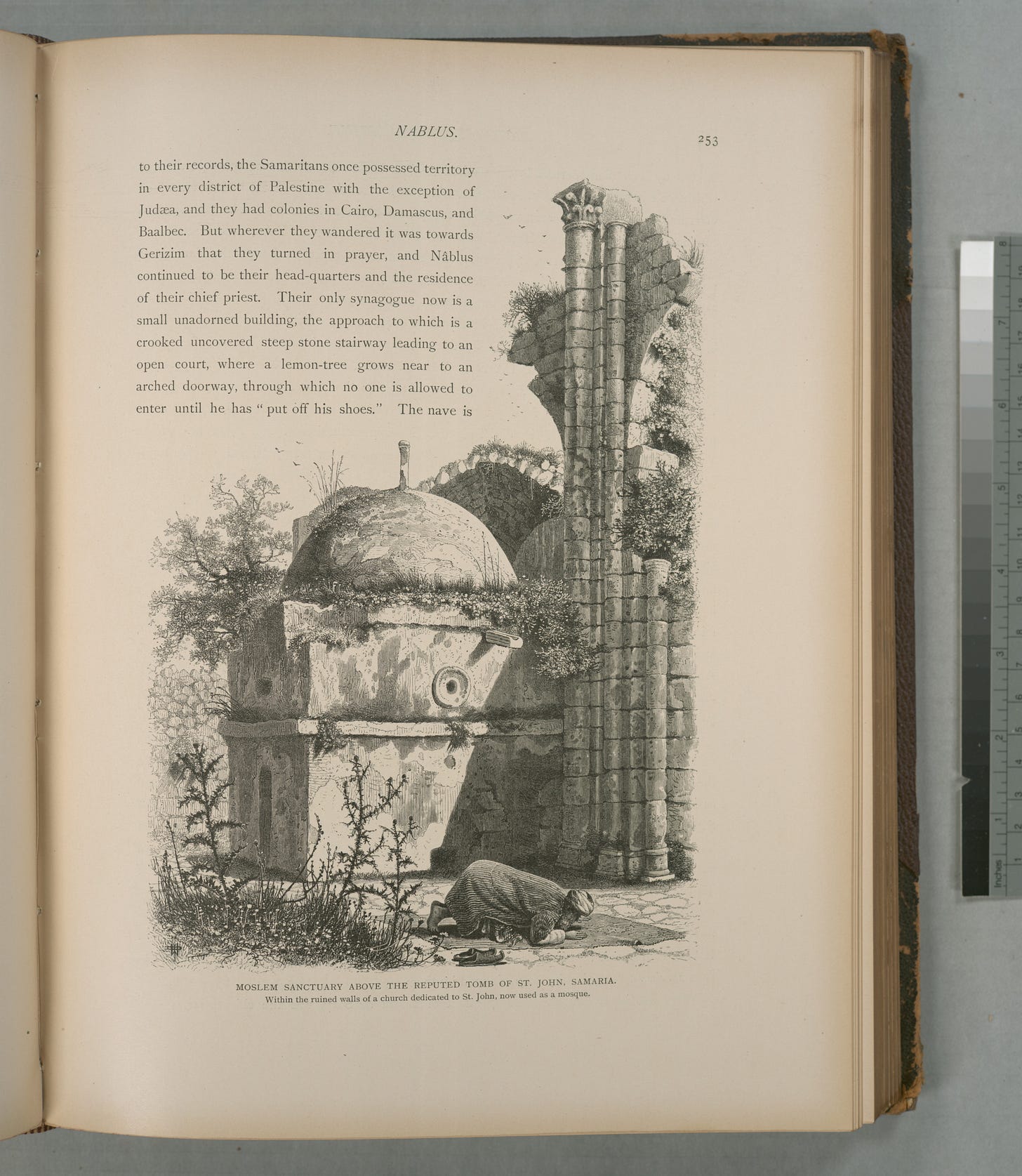

During the Byzantine period the city became the seat of a bishop and a number of churches were built commemorating the city as the birthplace of John the Baptist. A Byzantine church was built over his grave, on the ruins of the eastern gate of the ancient city. After the Arab conquest of 636 CE, this was replaced at different times with a Crusader church and the Nabi Yahya Mosque—the Muslims know John the Baptist as the Prophet Yahya. The mosque stands within the ruins of the larger church, which also is said to contain the graves of the prophets Elisha and Obediah; writing of the crypt in 1870, Victor Guérin stated that, “According to an ancient tradition, one of these compartments is the tomb of St. John the Baptist, and the others those of the prophets Obadiah and Elisha.”

The Palestine Exploration Fund’s Survey of Western Palestine described the Crusader church:

“The Church, a fine Crusading structure, over the traditional place of burial of St. John Baptist, is supposed to have been erected between 1150 and 1180 AD. It is now a mere shell, the greater part of the roof and aisle piers gone, and over the crypt a modern kubbeh has been built. The interior length is 158 feet, the breadth 74 feet; the west wall is 10 feet thick, the north wall 8 feet, the south wall 4 feet. There were six bays, of which the second from the east is larger, probably once supporting a dome. On the east are three apses to nave and aisles, the central apse is 30 feet in diameter, equal to the width of the nave. The piers had four columns attached, one each sid ; on the west was a doorway and two windows; on the south four windows remain, and on the north three. The nave had clerestory lights. The sixth bay is slightly narrower than the rest. The bearing is due east and west.

“The capitals resemble those of French twelfth century churches, but the cornice above is of semi-classic style, like that of the Nablus gateway. A sort of fortress appears to have been attached to the church on the north, flanked by square towers. The tomb in the centre is a small rock-hewn chamber, reached by 31 steps, and here the graves of Elisha and Obadiah are also shown. The masonry of the church is beautifully fine and perfect; the stones are of moderate size (about 1 1/2 feet high and 2 feet long), and are regularly dressed with a toothed instrument, but not always in the same direction. The masonry of the northern building is rougher, and drafted on the north wall. Between the south windows on the outside are buttresses 5 feet by 2 1/2 feet. The west door has a simple pointed arch, but the windows, though at a higher level, have round arches. The designs on the capitals differ considerably—smooth leaves, palm leaves, Corinthian volutes, etc. This is the case also at Ramleh. (See Sheet XIII.) The vaulting over the main apse is groined, with pointed arches beneath.

“There are a few crosses scratched on the walls, and some masons' marks were collected. For purposes of comparison they are here printed with others collected by Colonel Wilson.

“With regard to these marks, it is curious that one [shown below], which recurs several times, is very much more boldly cut than the rest, and generally larger, being on some stones about 2 inches long.

“Of this collection some are found in other dated buildings, viz. : Mûristân (1130-40), Lydda (1150 or later), Tomb of Virgin (1103). The marks are thus in many instances extended over a period from 1100 A.D. to 1180 A.D.”

The Survey of Western Palestine gives further details of the Crusader church, appending an extract from Captain Wilson’s letters referring to excavations carried on simultaneously at Sebastia and Mount Gerizim:

“At the former [Sebastia] some excavations were made at the Church of St. John and two of the temples. A plan was made of the church and the grotto, which seems to be of masonry of a much older date than the church. There are six loculi, in two tiers of three each, and small pigeon-holes are left at the ends for visitors to look in ; the loculi are wholly of masonry. The northern side and north-west tower are of older date than the Crusades—I think early Saracenic ; in the latter there is a peculiarly arched passage. The church is on the site of an old city gate, from which the "street of columns" started and ran round the hill eastwards. The old city was easily traced. Plans were made of the temples; they are covered with rubbish from 10 to 12 feet deep, to remove which with Arab labour would take some three or four months.”

During the Ottoman period, the site remained a small village. The French explorer, Victor Guérin, visited the village in 1870, which he found to have less than a thousand inhabitants. He described the church of John the Baptist. In 1882, the Palestine Exploration Fund’s Survey of Western Palestine described Sebustieh (as they spelled it):

“A large and flourishing village, of stone and mud houses, on the hill of the ancient Samaria. The position is a very fine one; the hill rises some 400 to 500 feet above the open valley on the north, and is isolated on all sides but the east, where a narrow saddle exists some 200 feet lower than the top of the hill. There is a flat plateau on the top, on the east end of which the village stands, the plateau extending westwards for over half a mile. A higher knoll rises from the plateau, west of the village, from which a fine view is obtained as far as the Mediterranean Sea. The whole hill consists of soft soil, and is terraced to the very top. On the north it is bare and white, with steep slopes, and a few olives; a sort of recess exists on this side, which is all plough-land, in which stand the lower columns. On the south a beautiful olive-grove, rising in terrace above terrace, completely covers the sides of the hill, and a small extent of open terraced-land, for growing barley, exists towards the west and at the top. The village itself is ill-built, and modern, with ruins of a Crusading church of Neby Yahyah [St John the Baptist], towards the northwest. Samaria commands two main roads, that from Shechem, to the north, which passes beneath it on the east, and that to the plain from Shechem, which runs west of it, in the valley, about two miles distant.

“A sarcophagus lies by the road on the north-east, but no rock-cut tombs have as yet been noticed on the hill, though possibly hidden beneath the present plough-land. There is a large cemetery of rock-cut tombs to the north, on the other side of the valley. The neighbourhood of Samaria is well supplied with water. In the months of July and August a stream was found (in 1872) in the valley south of the hill, coming from the spring (‘Ain Hârûn), which has a good supply of drinkable water, and a conduit leading from it to a small ruined mill. Vegetable gardens exist below the spring. To the east is a second spring called ‘Ain Kefr Rûma, and the valley here also flows with water during part of the year, other springs existing further up it. The threshing-floors of the village are on the plateau north-west of the houses. The inhabitants are somewhat turbulent in character, and appear to be rich, possessing very good lands. There is a Greek Bishop, who is, however, non-resident; the majority of the inhabitants are Moslems, but some are Greek Christians.”

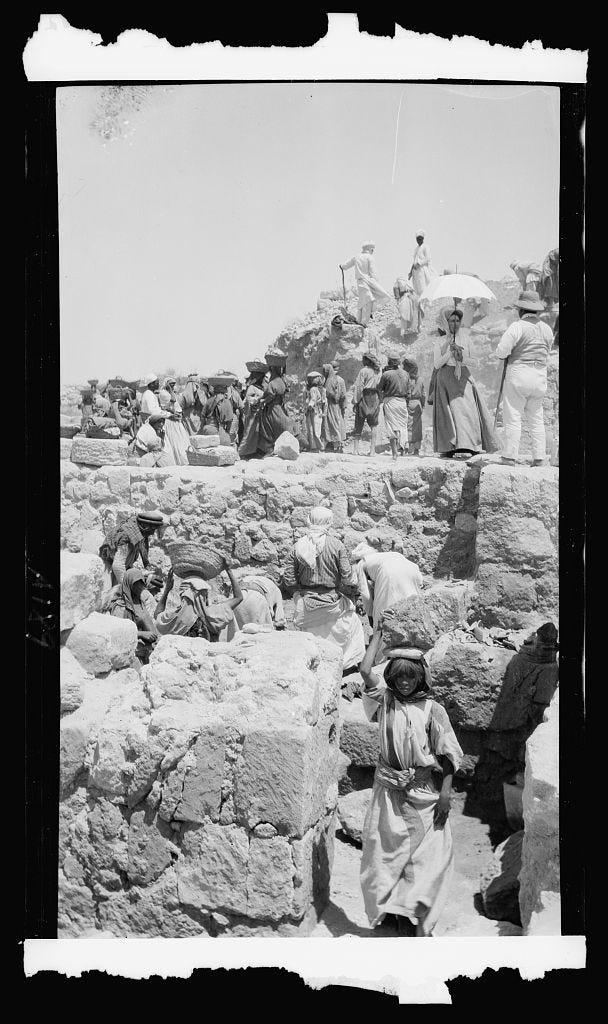

As is obvious from these descriptions, there wasn’t actually much to see at this time. The site was only excavated for the first time in 1908, by the Harvard Expedition, initially directed by Gottlieb Schumacher and then by George Andrew Reisner and CS Fisher in 1909 and 1910. Among other things, the expedition unearthed the 102 Samaria ostraca (ostraca are sherds or small pieces of stone that have writing scratched onto them), of which 63 are legible. The ostraca are written in the paleo-Hebrew alphabet. They were found in the treasury of the palace of King Ahab, and probably date to 850–750 BCE. They are currently held in the collection of the Istanbul Archaeology Museums.

The second excavation, known as the Joint Expedition, comprised a consortium of five institutions directed by John Winter Crowfoot between 1931 and 1935, with the assistance of Kathleen Mary Kenyon, Eliezer Sukenik and GM Crowfoot. The leading institutions were the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem, the Palestine Exploration Fund, and the Hebrew University. In 1965 and 1967, limited excavations were carried out by Fawzi Zayadine for the Jordanian Department of Antiquities, and in 1968—on the west side of the hill—by GH Hennessy.

Now for a brief tour of the parts of the site not already mentioned. The view of the valley to the north-east, from the forum—with the remains of the stadium in the distance marked by rows of pillars—shows the great extent of the ancient town.

The stadium was 200 metres long and 70 metres wide, and dates to the Herodian period.

The remains of the forum itself abut the modern village square, but the forum was originally about 128 metres by 73 metres, surrounded by walls. At its western end is a basilica which served as a gathering place for the inhabitants, and whose western apse served as a tribunal.

The Roman theatre dates to the third century CE; it was of 65 metre diameter with twenty-four rows. Above it rises the remains of the Israelite wall which encircled the fortress of the Kings of Israel. The magnificent Macedonian-style round tower—characterised by huge blocks laid radially across the width of the wall, narrower on its inside face—was built on its foundations in the Hellenistic period. This tower formed part of a wall around the city in that period.

We have already mentioned the Augusteum or Temple of Augustus. All that remains today are the steps and podium with its mighty column bases that would have supported a portico and pediment of immense size. The steps seen today date to a rebuilding of the temple during the reign of Septimus Severus, who reestablished the city as the colony of Colonia Lucia Septimia Sebaste in 201 CE. Although the restoration of the city retained the Herodian plan and buildings, the temple had apparently gone into decline and been used as a source of masonry. Severus restored the temple, using some of its original masonry. The temple stood amongst houses, and a large marble statue of the emperor Augustus stood in front of it in a large forecourt.

In the Byzantine period (fifth century CE) a church was built which—like that in the village in which there is now a mosque—claimed to mark the burial place of John the Baptist. It was restored in the Middle Ages (twelfth century) when it was part of a monastery. The crypt is still in use as a chapel, and the graves of the last Christians to live in modern Sebastia can be found outside the church. Despite this lack of resident Christians, Sebastia remains an Archdiocese under the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem.

Returning to the politics, it seems that nobody benefits at Sebastia. Interviewed in 2015, Mohammad, owner of the Holy Land Sun complex of hotel, restaurant and souvenir shop, which abuts the archaeological site, said he misses the pre-Oslo Accords days, when Israeli tourists flocked to Sebastia, bringing business with them. On the day of our visit he was once of only a few businesses open—or permitted to be open—in the square, yet few Israelis entered his store, or took camel rides from the camels ‘parked’ nearby: fear breeds fear, since there is no way to be sure if it is warranted or not. Mohammad’s customers these days are mostly Christian pilgrims, who come to pray at the ruined Byzantine church of John the Baptist.

As recently as January 2023, The Palestinian Authority paved a new road from the northern area of the village to the entrance of the hippodrome. The works ran through Areas B and C and, during the works on the road, a wall from the Herodian era was destroyed and burial caves from the Second Temple period were broken into and looted. This represents the practical aspects of the Palestinian leadership’s war to disconnect and even destroy Jewish history from the land, which in its theoretical aspect is represented by the information plaques and centre in the village (which Jews may not visit), which completely ignore the Jewish presence in the site, as described above.

Allegations are frequently made—as much by left-wing Jewish activists as by anyone—that the Israel Nature and Parks Authority equally ignores at least the Arab history of the site, if not all the non-Jewish or non-Biblical history, but we saw no evidence of this: both the official leaflets handed out and the guide made sumptuous mention of all periods and peoples involved in the story of the ancient city. And it is hard to talk about the more recent history since the Arab invasion, since there is literally little of note, simply because the city became a small and impoverished village.

Some weeks after our visit, it was reported in the press that the Israeli government approved a budget of NIS 32 million ($8.8 million) for the restoration and development of the Sebastia archaeological site, establishing a tourism center at the site, building new access roads, mapping untouched areas, and increasing law enforcement to prevent illegal activity, under the aegis of Israel’s Nature and Parks Authority. Although politics may have prompted the move, it must surely be a good thing that much-needed resources will be pumped into protecting, studying and promoting this much-neglected site. Whether or not the local population will have any involvement in the plan, however, may come back to politics on either or both sides.

Under the Oslo II Accords, Area A is under the full civil and security control of the Palestinian Authority (PA), Area B is under Palestinian civil control and joint Israeli-Palestinian security control, and Area C is full Israeli civil and security control.